The National Dispute

By the autumn of 1989, relations between the Trades Unions and the Thatcher government were at an all-time low. The Tories were determined to use their large majority in Parliament to crush the unions, and remove any power that they once had. Empowered by the guarantee of government support, managers in Ambulance Services all over the UK were standing firm against any requests for pay rises, or better conditions for staff. In London, the managers were going one better, introducing changes in working practices, with little or no consultation. It was all getting very serious, and we could see that it would soon come to a head.

One of the new demands was that we move from our normal place of work, if our crew-mate was off sick, or on holiday. This might seem reasonable, but the previous arrangement had relied on overtime being offered to staff on days off, ensuring a full complement of emergency ambulances was available in all areas of London. If one of us moved to another base, up to ten miles away, we would operate from there, leaving our normal station undermanned by at least one vehicle. This not only left the remaining staff with a greater workload, it also meant that the local population did not have the guaranteed vehicles available to them, in the event of an emergency. The decision on who moved, and where to, was left to Control Room staff, often with no operational experience.

Protracted pay negotiations had got nowhere, and there was already a limited work-to-rule in place. This simply meant that we did the job properly, by the rule book. We took vehicles to be re-fuelled, refused to operate without adequate supplies of oxygen, or with faulty equipment, and carried out all the necessary checks, before commencing duty. Any defects with the vehicles, normally tolerated for the shift, would result in that vehicle not being used. All of these were safety rules, and for the benefit of the patients. They were routinely flouted at other times, just so the workload could be managed, and always at the suggestion of the managers, who used guilt and custom as leverage. Another rule, also ignored normally, was that no Ambulance should be operated, under any circumstances, by one person. There was limited rearward visibility, and also the chance that you would be flagged down to attend an incident, when you were alone, and unable to properly assist. Working to rule meant that we refused to operate vehicles on our own, so could not travel to other bases in them. We could not use our own transport, if we had any, as this would have necessitated insuring our own cars for business use. Public transport was not really an option either, due to the location of some bases, and the long journey times involved.

In an atmosphere of antipathy, an attitude of non-cooperation developed, and this was made worse, by the belligerent attitude shown by some managers. Despite the problems over pay and conditions, and the many factors affecting our working lives, it was the issue of moving bases, which was to become the spark that ignited one of the longest, and most acrimonious disputes, in the history of the National Health Service. As the Union Shop Steward at my Ambulance Station, it also fell to me, to become the instigator of this whole dispute, as it just so happened, that on that day, I had nobody to work with. On that morning in September, I had no idea that the outcome of my decision would result in a bitter six-month dispute, that would see us through a harsh winter, with no pay; staff losing their houses, marriages breaking up, and deep resentments being formed. It would never be the same afterwards, and the long-lasting effects would stay with me, through a further twelve years of service.

When Control asked if I was fully crewed that day, I replied no, and asked them to find someone on overtime, to work with me on that shift. After a few minutes had passed, they called back, and instructed me to take the ambulance, and to report to Chiswick Ambulance Station, to work with someone there, who was also single-crewed. I refused, advising them that I was unable to use the vehicle on my own, by their own rules. I then telephoned the person at Chiswick, telling him to expect a call, instructing him to drive over to work with me, as I anticipated that this would be the next step. Sure enough, that was what happened, and he also refused to move, citing the same rules. They called me back, someone more senior this time, and gave me a ‘direct order’ to do as they asked. I refused once more, and I was told that I would be suspended from duty, pending disciplinary action. Ten minutes later, the same scenario was played out with the man at Chiswick, and within an hour of starting work, we were both suspended, and potentially unpaid, unless we relented, and agreed to move.

I advised the other crew members on my station, and at Chiswick, and they all withdrew their labour, in support of both of us, demanding that the suspension be withdrawn, and the threats rescinded. I then contacted the next nearest base, at St john’s wood, and told them what was happening. They in turn, contacted Camden, Willesden, and Park Royal, and before long, almost the whole of West London was ‘on strike’, until we were reinstated. This soon got through to the full-time union officials, and the local media. I gave an interview to the local TV news programme outside the Ambulance Station, explaining the reasons for the action, and it was shown at lunchtime, and again that night. By now, we were occupying the bases, and the unions were running scared, fearful of having their funds sequestered, as this was unofficial action. They tried to get me to return to work, pending negotiations, but they were overtaken by events, as the dispute spread all over Greater London, the staff angry and frustrated by management attitudes, and frightened unions.

During the rest of that day, we had local meetings, and agreed that we were not on strike, and that we were still prepared to answer emergency calls, based on the terms and conditions that preceded the current dispute. However, the managers had seen their chance to break us, and refused to pass calls to the individual bases, telling the media that we were on strike. They began to use the Police, and called in volunteers from the Red Cross, and St John Ambulance, to respond to calls. They also used private ambulance companies for non-emergency work, and tried to portray themselves as the unfortunate victims of union agitators. Some operational managers took vehicles from Headquarters, and attended calls. We put up posters and banners, advising the public that we were still working, even though we were not being paid, and we gave them direct phone numbers, so they could ring in straight to us. We also told the Police and the local hospitals the same thing, and by the time night duty arrived, we were answering calls at our own instigation.

Some staff were still working normally, refusing to cooperate with their colleagues. Some had political, or religious reasons, some were scared of not being paid, and others just disliked some of us who were seen to be on strike. They had to be moved, so that they all worked in the same area. They were in no danger from us, we just lost respect for them, and they were never fully accepted again afterwards. They were surprisingly few in number, with the dispute, as we began to call it (as we were not on strike) gaining overwhelming support from the vast majority of staff. The whole thing escalated, and began to go national. Staff in all parts of the UK were joining in, and soon the unions could no longer ignore the overwhelming feelings of their members. In most of the major cities, solidarity was total, and we all still made our best efforts to provide cover for emergencies. Some bases actually attended more calls during some parts of the dispute, than they had when working normally.

This soon became front page news, and the first item on all the TV news stations. Government ministers were interviewed, union officials gave our side of the argument, and cameras appeared outside casualty departments, and the larger ambulance stations around the country. To the surprise of our management, the Government, and to some extent, those involved on the ground, the general view was sympathetic. Members of the public supported us overwhelmingly, and ninety percent of media reports were also very favourable. We were seen as the maligned carers, the professionals who put up with low pay, little recognition, and carried on uncomplainingly. For us to be in dispute, something bad must really be happening. The public believed in us, the hospitals believed in us, even the Police believed in us. It was left to our own management, and Tory politicians, to spread untruths about our motives, and to paint a picture of us as ungrateful strikers, callously disregarding the unfortunate sick and injured. Everyone wanted us to be paid more, and to receive decent conditions too. Opinion polls suggested massive support, and there were suggestions for a plan to pay more taxes, or higher National Insurance, to fund the changes, and to put an end to the dispute. The managers were on the back foot, and the government under pressure. They reacted spitefully, as you might expect.

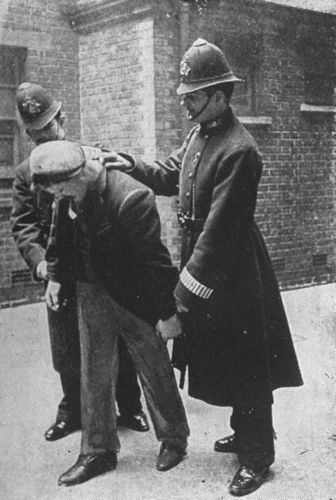

Our occupation of the bases was declared unlawful, and they tried to get us evicted for tresspassing, but could find nobody willing to enforce this. They then technically sacked us all, withdrawing our right to use the ambulances, and the equipment owned by the services involved. They reported us to the Police, for ‘stealing’ ambulances that we were using to respond to calls. Again, the Police refused to enforce this, not wanting any part of a dispute that had caught the imagination of the public, who had soon realised that we were not actually striking. The attitude of all the staff was indeed admirable. Everyone continued to turn up for work, and to man all the shifts, even the most unsocial ones. Those on days off turned up anyway, to help with the occupation of the buildings, talking to the public, and answering the telephones. As the weather got colder, we had braziers burning to keep warm, and people turned up unannounced, with wood for the fires, and gifts and food for the staff. People also began to give us money. At first, we declined, feeling uncomfortable about this. We did get some hardship pay from the unions, but it was only a small amount, nowhere near enough to survive on. The donations were used to buy badges, stickers, and information leaflets, all handed out to the public, to advise them of our reasons for the dispute, and to ask them to wear the badges and stickers, to show support.

Staff began to attend busy areas with these; outside main railway and tube stations, at major junctions, like Oxford Circus, and also busy street markets, in our case, Portobello Road. We took banners, and boxes of badges, and we were soon overwhelmed by cash donations. From old ladies emptying their purses, to local celebrities giving wads of notes, the money started to flow in. By December, at least in London, we were receiving sufficient donations to almost pay staff the same wage they got when working normally. This stiffened our resolve, and made the earlier hardships seem worthwhile. With this continued level of support, we felt sure that we could win.

Without us ever imagining it, we were taking part in the most popular dispute in union history. We felt that we owed it to the public to continue, and we owed it to ourselves too.

Day to day, life was still hard. Staff divided into three groups. One would work on the ambulances, answering those calls we got through. Another would occupy the base, picketing outside, keeping the braziers burning, and putting on a brave face for the public. The third group would go and stand somewhere, advertising the dispute, receiving money from donations, and distributing badges. We had caps made as well, with our slogans on them, and often family members would assist too, standing with their husbands and wives, or mums and dads, showing solidarity with our cause. Each week, the donations would be divided, those with bigger families, or larger mortgages, getting the biggest shares. The meetings continued, locked in stalemate. The media kept the story alive, but also reported the tragedies that had happened, hinting that they might not have happened, if we were working normally. Army ambulances were brought in; unsuitable vehicles, doing an unfamiliar job, escorted by Police cars, as they did not know the areas. The managers, and more importantly, the government ministers, refused to budge on anything unless we first returned to normal duties. We endured a very cold, and miserable Christmas, with little hope held out, for a resolution in 1990.

Amazingly, public support never wavered. The donations kept coming, and the kind words too. We started the new year in an atmosphere of grim determination, on both sides. By now, former colleagues in supervisory roles had become bitter enemies. We no longer spoke to any managers, or control room staff. There was no local negotiation, of any kind, and all meetings were being held by union officials, with NHS management, and government ministers. We had become detached from the process, trying to deal with daily survival. I developed a deep personal hatred for some individuals, and for the voluntary workers, who were taking holiday time, to do our jobs when we were in dispute. For me, that never diminished, and remains with me, to this day. On the other hand, we formed bonds and friendships as well, with hospital staff, some police officers, and colleagues, that are unbroken as I write. Over 200.000 people attended a rally of support in Central London, and large events like this were seen all over the UK.

By the end of February, the unions were beginning to buckle. The management was willing to concede some points, but pay increases were a national issue, controlled by the government, and that was intransigent. Leading union officials began to hint at a possible solution, and this was accelerated by renewed media interest. The staff wanted none of it. We wanted to hold out, for all the reasons we had started on this five-month dispute, and could see no point going back to working normally, unless we got all our demands. The volunteers doing our job were running out of time, and would have to go back to their normal jobs. The cost of paying the police and army to carry on was prohibitive. The total costs of the dispute already far exceeded what it would have cost to settle in the first place, but they would not back down. After meetings at the end of the month, the NUPE union leader, Roger Poole, announced that an agreement had been reached, and that we would return to work in March, six months after we began the work to rule. He didn’t think to ask us what we thought. He famously announced on TV, that he had ‘driven a coach and horses through Tory pay policy’. And he wasn’t even embarrassed. What he failed to add, was that he had agreed, on our behalf, to accept the derisory pay increase that we had been offered originally, and that he had also agreed to the changes in conditions and practices that had brought us to this in the first place.

Some staff, me included, wanted to ignore the unions, and carry on. But there was no widespread support for this, and that was understandable. Some staff had suffered marriage break-ups, others had seen their homes repossessed. Many had just left, or resigned soon after, broken and disillusioned. All of us had endured six months with no pay, dependent on public goodwill from donations, and sticking through a harsh winter, with no end in sight. We went back to work in March, as if nothing had happened; though some people were shunned, others transferred by request, and some managers moved around. Our relationship with the unions was never to be the same again. I left the NHS union, COHSE, and joined TGWU, as a small personal protest. I had also stopped being the union rep for our base, as I had simply had enough at the time, though I did do it again, later on. We had lost, and it wasn’t a good feeling.

Or had we?

Within a short space of time, most of the old management was gone. Pushed out, retired early, or plonked behind obscure desks. Our public profile was raised beyond recognition, and training was brought into the 20th Century, with new skills, new equipment, and modern vehicles. Paramedics and Technicians were beginning to be portrayed in TV programmes, as an essential part of the emergency services, and as having a vital role in the NHS. They were filmed in documentaries, the often thankless job shown for all to see, actually as it happened. Other branches were introduced, rapid-response vehicles, motorcycles, and even a helicopter. (Actually run by the London Hospital) By the year 2000, ten years after the dispute ended, the job was being paid at a fair rate, and finally given the respect it was always due.

I don’t believe that this would ever have happened, without those six months of hardship, between 1989-1990. I am proud to have been a part of it, and always will be.

0.000000

0.000000